The History of Sport Climbing

The History of Sport Climbing

gearweare.net

The History of Sport Climbing

gearweare.net

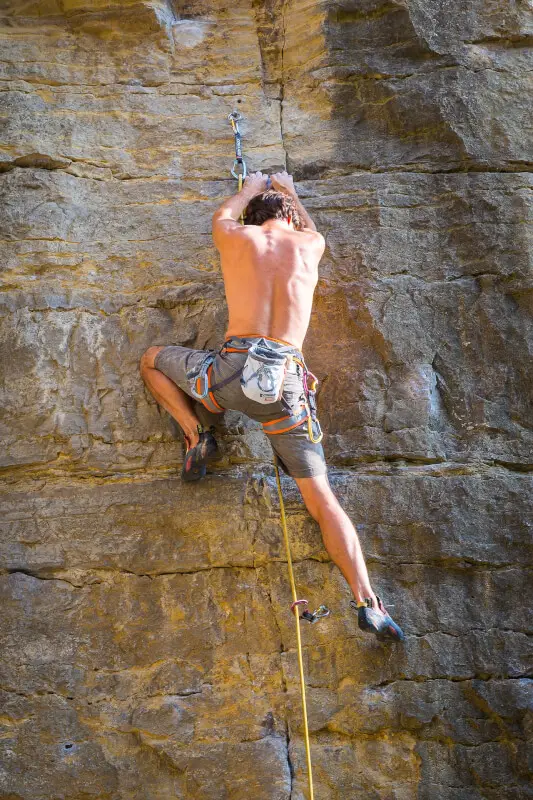

The different styles of rock climbing that are now commonly accepted among practitioners of the sport have only evolved over the last few decades. Before the 1980s and 90s, climbing was just climbing. However, the proliferation of bolted routs that came out of this time necessitated the designation of “trad climbing” vs. “sport climbing.”

When sport climbing began to gain popularity, it was greeted with resistance by many old-school climbers. Still, there was a natural progression at work here that cannot be denied. Sport climbing has allowed for the development of harder and harder routes. Without this style of climbing the current pinnacle of 5.15d may have never been reached. It also allowed for a wider range in development. Before sport climbing, cracks were needed to protect a rout, making interesting face climbs impossible for anyone who wanted to avoid a potential ground fall. The use of bolts, a defining feature of sport climbs, changed this. Suddenly seemingly featureless slab, interesting arêtes, and large, overhung roofs, became fair game for root development.

The rise of sport climbing took place during the late 70s, 80s, and into the 90s in both Europe and the US. The transcontinental movements may have influenced each other, however each was distinct. The European movement began a bit sooner in the Verdon Gorge, a gorgeous canyon in France that is often compared to the Grand Canyon. Meanwhile, Oregonian climbers who frequented Smith Rock began to push the limits of hard sport climbs in the US. From these two areas this style of climbing has spread. Although there are still some traditionalists who see sport climbing as a lesser form of climbing, most now accept it as a valid way to enjoy the sport.

Verdon Gorge

Located in southeastern France, the Verdon Gorge gets its name from the bright turquoise river of the same moniker that formed it many years ago. In some areas, the walls of this impressive canyon extend from the rim to depths well over a thousand feet. Most of the hundreds of climbs located here can only be reached via rappelling. Roads along the edges of the gorge make this far more practical than bushwhacking along the river. However, approaching the climbs from above also makes rout finding more difficult and dangerous. The Verdon is not a place for beginner climbers.

Climbing in the Verdon began in the 1960s, but was at first confined to alpine style ascents using cracks for protection. The large areas of blank rock between the cracks seemed impossible to climb. Even if some areas were protectable using cams, nuts, and pitons, it was not possible to tell from the ground if this held true along the entire rout. The possibility of reaching a point where no new protection could be placed kept the pioneers of the Verdon off much of the areas rock for many years.

This all changed in 1976 when Stephane Troussier and Christian Guyomar decided to investigate the “blank” walls by repelling into the Verdon Gorge from the top. Up until this time, the dominant ethic within climbing was that all routs should be approached from the bottom up. Repelling into a climb was seen as cheating, a negation of the spirit of adventure that defined the sport of climbing.

What Troussier, Guyomar, and other local pioneers found was a plethora of incredible rock features that could be linked together in ways seemingly designed for human ascents. Jacques Perrier really cemented the top-to-bottom approach of rout development. He would repel down a section of rock, working out the movement and best place to put bolts as he did so. This method set the precedent that climbers would begin to use for bolting sport routs around the world.

Spacy bolting and the potential for massive falls are the norm at the Verdon. Bolts are usually placed 10 to 30 feet apart. Although this may sound terrifying by modern sport climbing standards, it makes sense for the time, when protection was minimal across the board. It also makes sense because of the length of the routs, so newer routs follow this standard as well.

Smith Rock

In the US, Smith Rock is considered the birthplace of sport climbing. This now famous area first began to be frequented by Pacific Northwest climbers in the 1930s and 40s. By the end of the 70s all the big aid ascents had been done, and moving into the next decade free climbing* began to become more popular.

Driving the development at Smith Rock during the 1980s was a group of students from the University of Oregon. After they had all done the already established crack climbs, they began searching for new and harder ways up the rock. Alan Watts, who eventually wrote the guidebook on Smith Rock, and the rest of this crew started looking at the featured rock faces for routs, utilizing the same bolting techniques employed by the French in the Verdon.

By 1986, Jean-Baptiste Tribout had sent To Bolt or Not to Be, 5.14c, and Smith Rock became home to the hardest rock climb in North America. The difficulty of the climbing became impossible to ignore, and cemented sport climbing’s status as a new way to rock climb. As this sub-discipline has grown it has drawn in people of more varying abilities. There are now 1,800 bolted routs at Smith Rock, most of which are moderates (5.8-5.10).

The methods for rout establishment that the Smith Rock climbers used worked as a blueprint for the growth of other sport crags around the country. Shelf Road and Rifle, both in Colorado, American Fork in Utah, and The New River Gorge in West Virginia are just some examples of sport climbing areas that based their development tactics on what they saw at Smith Rock. Today, these methods have been perfected and sport climbing has grown to become the most popular way to climb.

*Remember, free climbing means ascending the rock using hands and feet only and is not the same as free soloing.